It almost goes without saying: in some Indy neighborhoods, when a developer proposes a new project, a certain contingent immediately assembles to oppose it. We probably all know which neighborhoods these are. While an article that calls these opponents to the carpet will seem unfair (and, at least on an urban advocacy blog like this, all too commonplace), I hope I can at least offer a little bit of nuance and balance to the investigation, while still making the fundamental claim that the proposal in question is a good one—which, in turn, means that opposing it is, in my opinion, not a very good idea from a long-term neighborhood economic development standpoint.

The development in question is taking place on the edge of the Chatham Arch neighborhood. Kevin here at Urban Indy already covered it several weeks ago, and it generated a fair amount of positive discussion, as well as some vocal opposition. The project, taking place at the corner of 9th Street and East Street (predominantly fronting the latter of the two) involves a mixture of apartments, townhomes, single-family homes, and approximately 2,000 square feet of retail. The developer is a former resident of Indianapolis, who bought the property several years ago: a vacant charter school, surrounded by an unlocked chain-link fence, which, in turn has allowed it to serve as a de facto dog park, as Urban Indy pointed out.

A few weeks after our article, the Indianapolis Business Journal covered the Chatham Arch Neighborhood Association’s (CANA) overwhelming opposition to the proposal, with 26 rejecting and only 3 favoring it. The general consensus is that the proposal is too much density—that the five-story apartment buildings in particular would loom over neighboring single-family homes, that parking is already scarce, and that the appearance is completely out of character with the cottages that comprise the historic essence of Chatham Arch. About this same time, the Urban Times monthly newsletter released a similar article, much more focused on the perspectives of the members of the Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission (IHPC). The IHPC voiced little concern about the proposal’s density but acknowledged some potential problems with how well it would conform to the appearance of the surrounding homes. By early December, the IHPC opted for a continuance, after determining that the architect/developer had not satisfied all the changes to the site plan that it requested through a November preliminary review.

So here we are, awaiting the next IHPC consideration on January 4, with CANA re-affirming its profound opposition to this proposal. Meanwhile, the Renaissance Place Homeowners Association, whose district sits just to the southwest of this site, objects primarily to the proposal’s pursuit of a variance for reduced parking, “in light of growing parking problems in the area” (per the Urban Times article). In other words, the voice of the surrounding neighborhoods, as least as articulated through neighborhood associations, is that this proposal is an unwelcome intrusion.

But what is the historic essence of Chatham Arch? It includes some of the oldest surviving housing in the city, with a few homes and commercial buildings dating from shortly after the Civil War, though the development of the neighborhood seems to have peaked in the 1880s to 1910s. Most of the approximately 110 structures contributing to Chatham Arch’s status as a nationally registered historic district date from that window of time. An optimal block in Chatham Arch looks like this:

Or this:

The neighborhood also features sporadic multifamily and commercial buildings.

And, since it did grow over many decades, it should come as no surprise that the homes feature a variety of architectural styles, sizes and building materials.

This tradition continues with the iterative infill from more recent decades—the era of Chatham Arch’s revival—which approaches contemporary design from a variety of interesting angles.

The modest appearance of many of the homes suggests that it never intended to be an enclave for the extreme wealthy. And, while it still doesn’t necessarily have the reputation of being a ritzy area per se, Chatham Arch commands some of the highest home values in the Indianapolis metro, at least when measured on a price-per-square-foot basis. Its strategic locations less than a mile from the city center and just blocks from Massachusetts Avenue has made it an extremely attractive location, and this desirability becomes manifest through steadily rising real estate values. (And many of the more recent homes are comparatively huge—sometimes twice as big as the historic neighbors.)

But is the area getting too big for its britches? That almost seems to be the implicit argument that CANA is posing: that the new development within Chatham Arch, and certainly in the less scrutinized blocks that surround it, is usurping the neighborhood of its original charm. And, as is almost always the case, the “density” argument rears its head. How dense is too dense? The developer with the proposal at 9th and East argued before the IHPC that Chatham Arch’s current density, at approximately 6,000 persons per square mile, is a far cry from the 20,000 persons a century ago, when the neighborhood burgeoned. Without confirming these numbers (it’s difficult determining how his Chatham Arch boundaries coincided with Census records from that time, when precinct or tract-based data lacked detail), he still made a compelling argument. After all, household size has been shrinking steadily for a century, which means these modest 1,000-square-foot homes, which today typically house only two or three people, probably used to shelter five or six. And if the number of people living in a typical house shrinks by 50%, it’s inevitable that the density in the overall neighborhood would shrink proportionally.

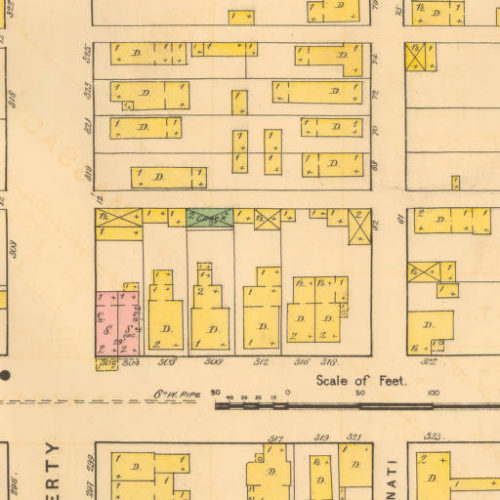

But that’s not it. An Indianapolis Sanborn map from 1887 shows exactly how tightly-packed the homes were back then.

Virtually no parcels were more than 50 feet wide along their primary street frontage, and many were only 35’ wide. The rare parcels that exceeded 50 feet usually hosted twins. But today? My photos up to this point have captured some of the blocks in Chatham Arch that best preserve the density from 1890. Most, however, fall far short.

This yawning space between two homes probably serves as a side yard to one of the two, but it shows on Google Maps and those Sanborns as a discrete parcel—one that undoubtedly supported a home at one point. And these side yards are scattered throughout Chatham Arch.

I will hand it to the current homeowners: in most cases, the curators of these side lots have done a marvelous job.

It’s a beautifully appointed garden, giving added texture to what otherwise would serve as a corner lot. And, in the residential market, corner lots are often the hardest to sell and lowest in value. But the side yard has also helped to make room for an enormous garage in the back alley, thereby essentially shutting out the prospect of the parcel getting developed.

The homeowner who built this garage showed remarkable fidelity to the original architectural language, so it conforms nicely with the house and may even serve as a granny flat. But the odds are slim that this garage dates from the same era as the home, which almost definitely predates automobiles.

The net effect of all these side lots is an aggregate loss in population density. Here’s another where the former home serves as a parking lot to the business to in the far left of the photo.

As a result of these side yards and the occasional parking lot, Chatham Arch, with an estimated density of 6,000, is simply average: high density for Indianapolis standards, but hardly on par with New York or Chicago, let alone many neighborhoods in older cities like Cincinnati or St. Louis. And its not evening within shooting range of its density from the time period where it once flourished—an era, we might assume, when the neighborhood’s biggest advocates would seek to re-affirm.

These observations strive to address one key underlying issue: the historic integrity that CANA and most other neighborhood associations strive to protect is predicated upon a highly precise chronological snapshot that the existing residents (and CANA members) themselves have cultivated. Such activism has its clear benefits: most likely it saved many structures from demolition when the neighborhood was still in decline in the 1970s. The advocates that eventually formed CANA helped save a district that now has achieved registration with the National Park Service. Perhaps a CANA in 1950 would have saved even more charming old homes, if it had existed. But we can’t allow alternative, speculation-based narratives to obfuscate our reconciliation of the reality at hand with the selective ideal. The anti-density arguments now are, in most respects, preventing Chatham Arch from achieving a recovery to the neighborhood’s conditions from its peak. The opponents want the charm, the “character” without the density. Given technological and household changes over the last century, I don’t expect Chatham Arch will ever again achieve 20,000 persons per square mile. But it’s not unreasonable to expect half that amount, given the development potential in the area—development that could, and should, resemble the type proposed at 9th and East.

Yet, time and time again, the remonstrators just won’t have it. When is dense too dense, and what time period are they trying to reinvent? The reality becomes clearer when we assess the vacant charter school parcel in question with its immediate surroundings, which I will do in the second half of this involved article. This article is getting too long, and my ideas are not yet fully formed…but they will be soon. In the meantime, I hope and expect this article to generate good discussion. I’ll try to participate when I can, though long-distance travel over the next few days may keep me away.

And stay tuned for part two.

[Note: A robust collection of old Indianapolis Sanborn maps is available here.]